Introduction

In this essay I will be using Marxist theories to discuss the Modern Art Market in deciphering the part of a painting that makes it so impressive as a commodity of exchange. To me, the fundamentally flawed quality of a painting is its utility as an asset, and how wealthy capitalists are able to exploit this quality as a medium of investment to circulate and grow their own capital, perpetuating a system of class elitism. To make sure my argument retains modernity, I will be using two essays, ‘The Coming Exception: Art and the Crisis of Value’ by Sven Lutticken and ‘Artistic Labour and the Production of Value: An Attempt at a Marxist Interpretation’ by Jose Maria Duran, to reweave Marxist economic theory into modern issues. I also wish to convey the fetishization of the painting commodity and the artist as intellectual proprietor. I will extract examples of the topics discussed in various paintings, such as Andy Warhol’s ‘Soup Cans’ and the Rembrandt painting created by a computer. To start, we first must understand the dual nature of a painting, from there we will discuss the over fetishization of the painting and its producer to finally help us understand how the Modern Art Market has become the institution it is today.

The Painting as a Commodity and Asset

Commodity

In Marx’s Capital in the chapter ‘Commodities and Money’ he states that, ‘The commodity, is first of all, an external object, a thing which through its qualities satisfies human needs of whatever kind.’ (underline mine)[1] This is a commodities ‘use-value’ and Marx says, ‘The usefulness of a thing makes it a use-value’[2]. Art, the industry of creativity and imagination, is not as grounded to physical use-values like science. This does not mean it is unnecessary. As said by Braque, ‘art is made to disturb, science to reassure.’[3] The ways in which a painting is useful is a matter of opinion. For example, Russian author Leo Tolstoy calls painting, ‘a means of union among people, joining them together in the same feelings, and indispensable for the life and progress towards well-being of individuals and of humanity.’[4] Marcus Du Sautoy states, ‘Art does many things, but for me where art is at its best is in providing a window into the way another mind works.’[5]

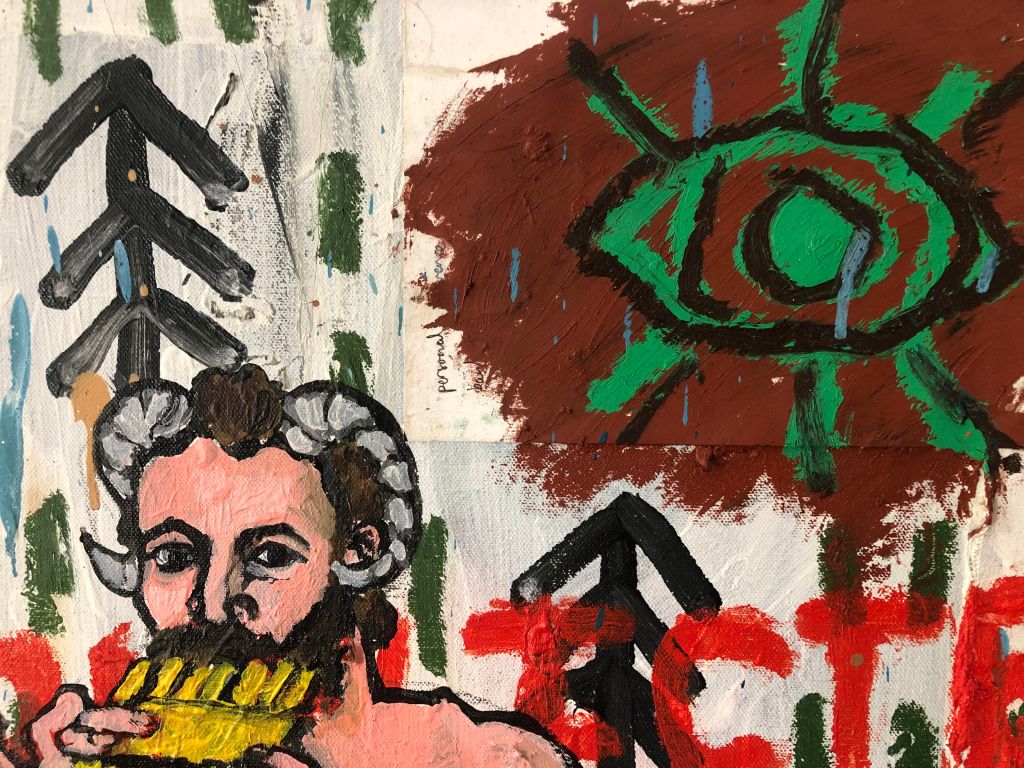

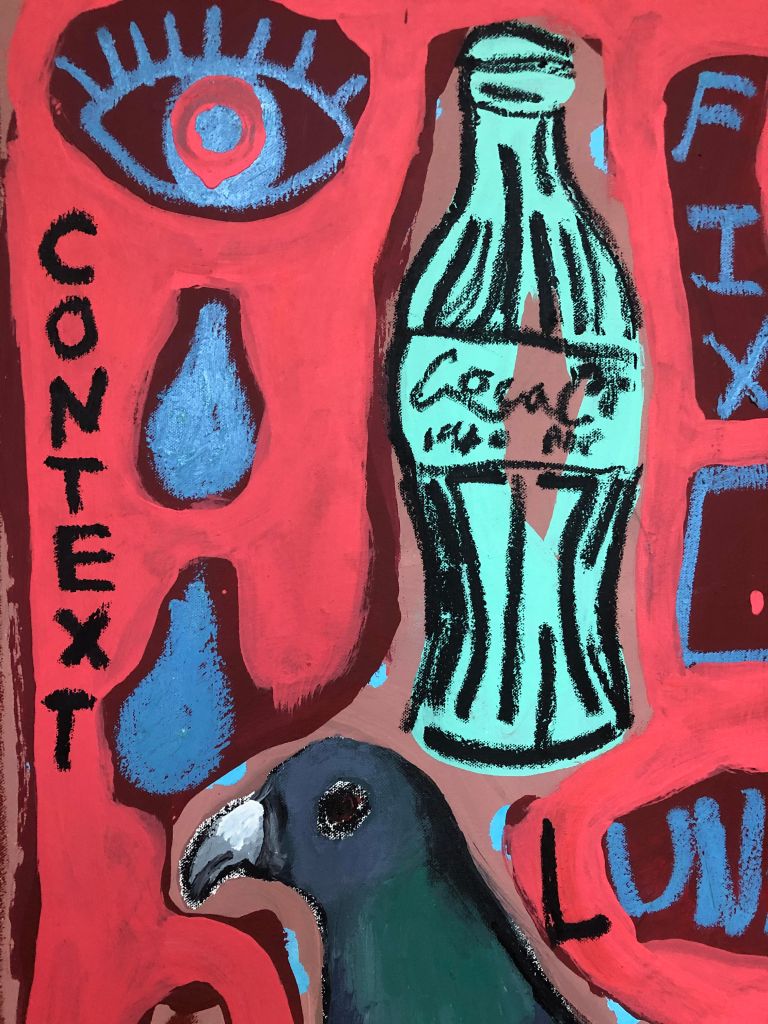

To me, paintings are decoration and an assertion of one’s intellect and existence. The raw canvas is a playground for the artist to throw their heart and soul into any form of colour and shape they desire[6]. The viewer then recognises this aesthetic value created by the artist and manifests an emotional connection with the piece, allowing for introspection and the creation of new ideas and concepts, like an idea generator.

Whether the artist wants it to or not, the piece always correlates to the context in which it was created, providing an anecdote for the times. This brings to mind a quote by James Mark Baldwin, ‘All along we find that social life – religion, politics, art – reflects the stages reached in the development of the knowledge of self; it shows the social uses made of this knowledge.’[7] It is in this sense that art acts as a historical catalogue, and the way in which this lineage is propagated and recorded is through the financial supervision of rich benefactors that utilise paintings for their exchange-value, a term I will discuss later on, rather than its historical significance[8]. As said by Marx, ‘Commodities… have a dual nature, because they are at the same time objects of utility and bearers of value.’[9] Paintings behold a dual nature in many respects. They are both decoration and vessel for new ideas, and an assertion and a reflection. In this essay I am analysing them as both commodity and asset. It is this latter quality that I will discuss presently.

Asset

As an asset, paintings are valuable for their ability to have an extremely high exchange-value compared to their physical use-value. On exchange-value, Marx says, ‘Exchange-value appears first of all as the quantitative relation, the proportion, in which use-values of one kind exchange for use-values of another kind.’[10] Paintings are therefore characterised by their seemingly abstract use-value and extremely lucrative exchange-value, allowing the capitalist to accumulate large amounts of profit from their redistribution in the marketplace. The circulation of the commodity is what generates its value[11]. As said by Jose Maria Duran in their essay[12], ‘Value is established in the market and it has no existence prior to it.’[13] It is when assessing this that we understand Marx saying, ‘Commodities are merely particular equivalents for money.’[14]

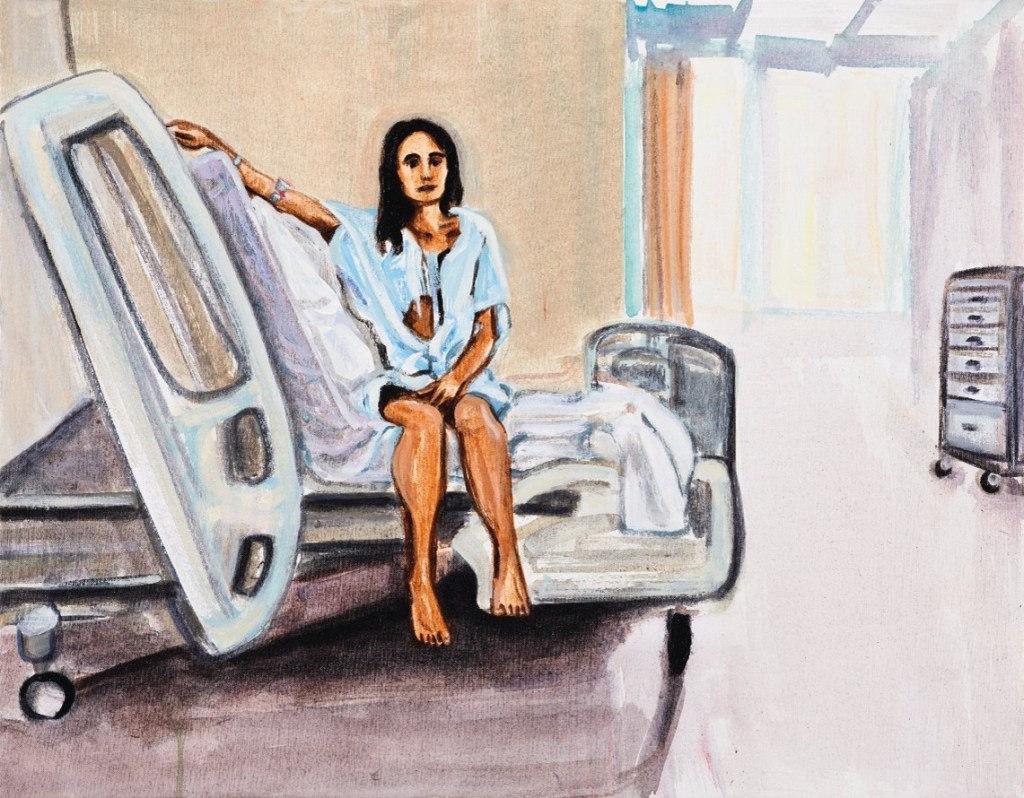

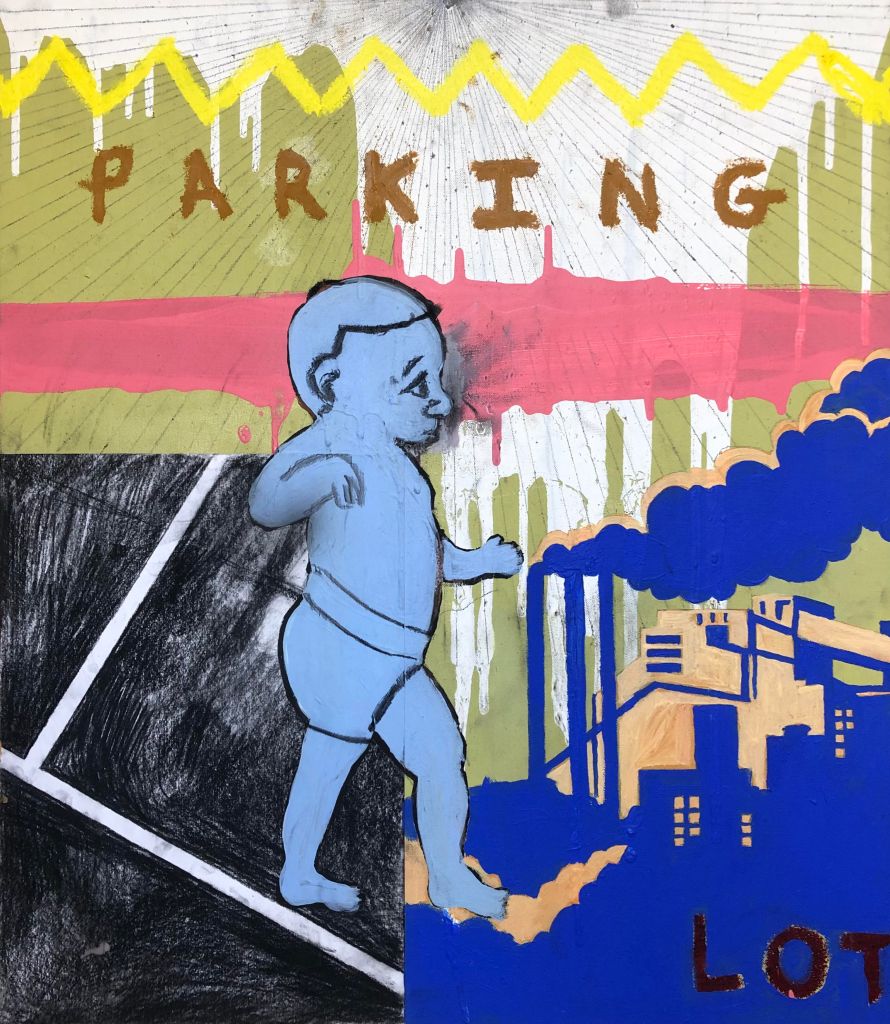

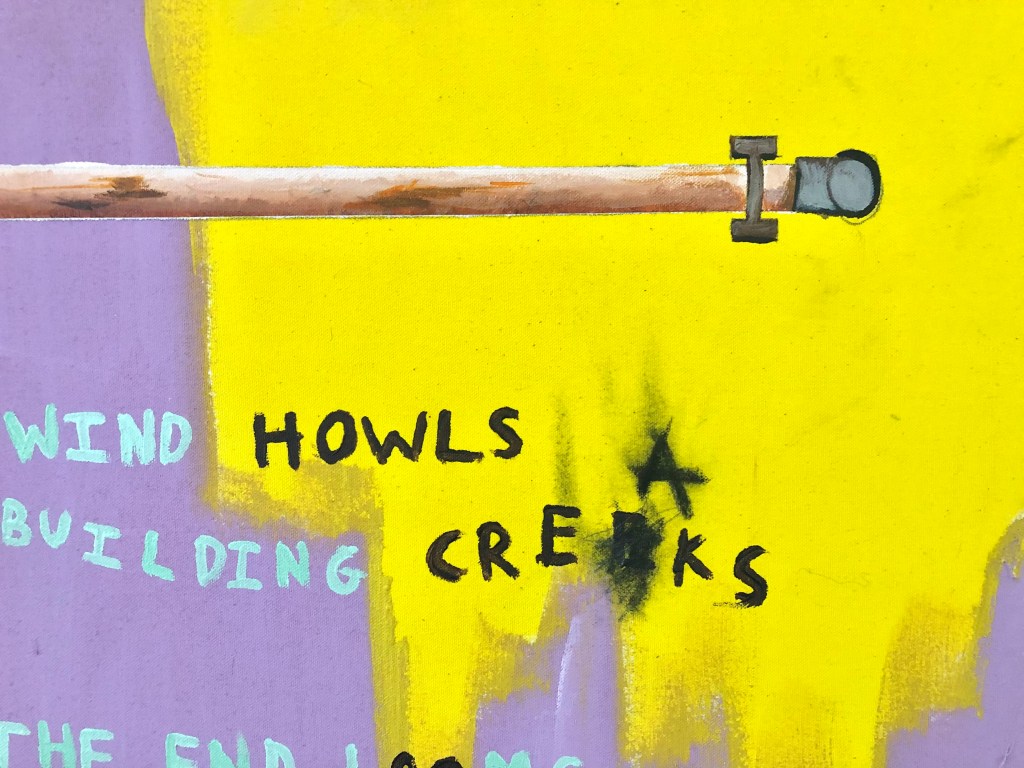

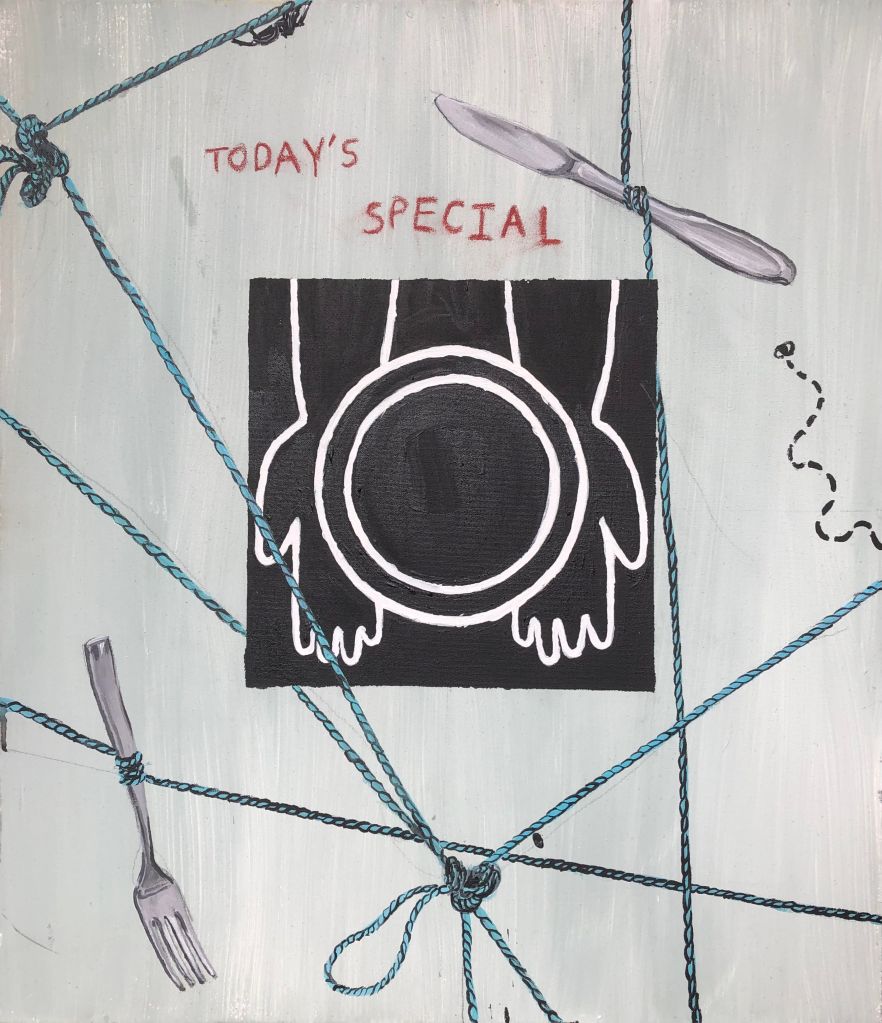

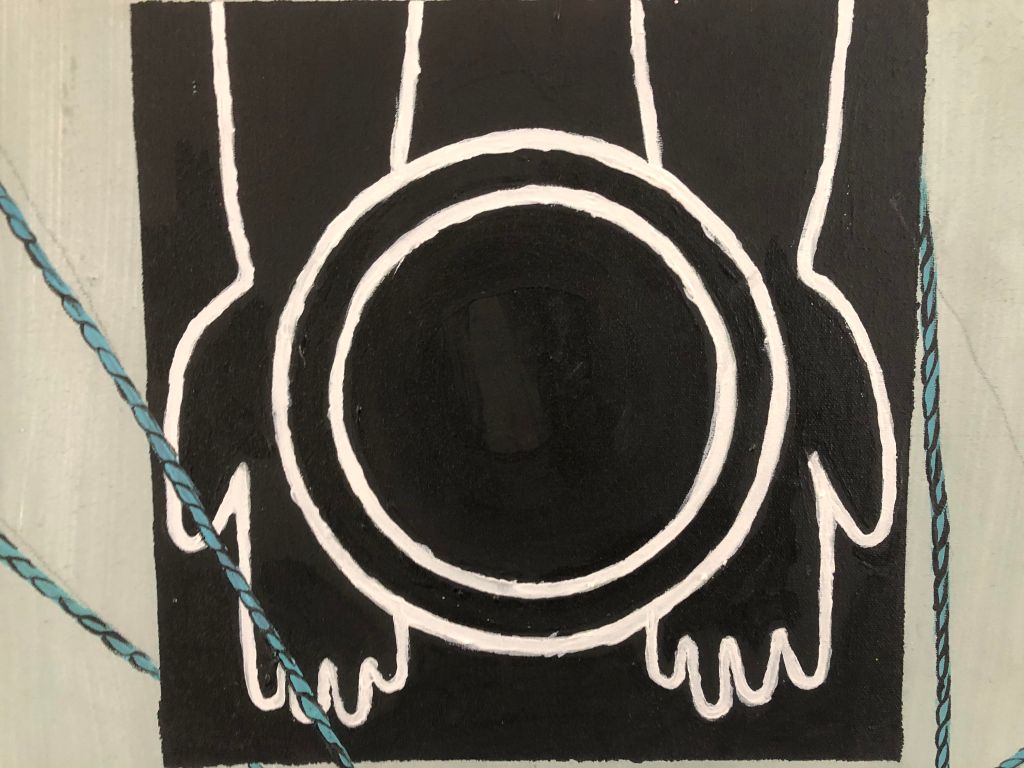

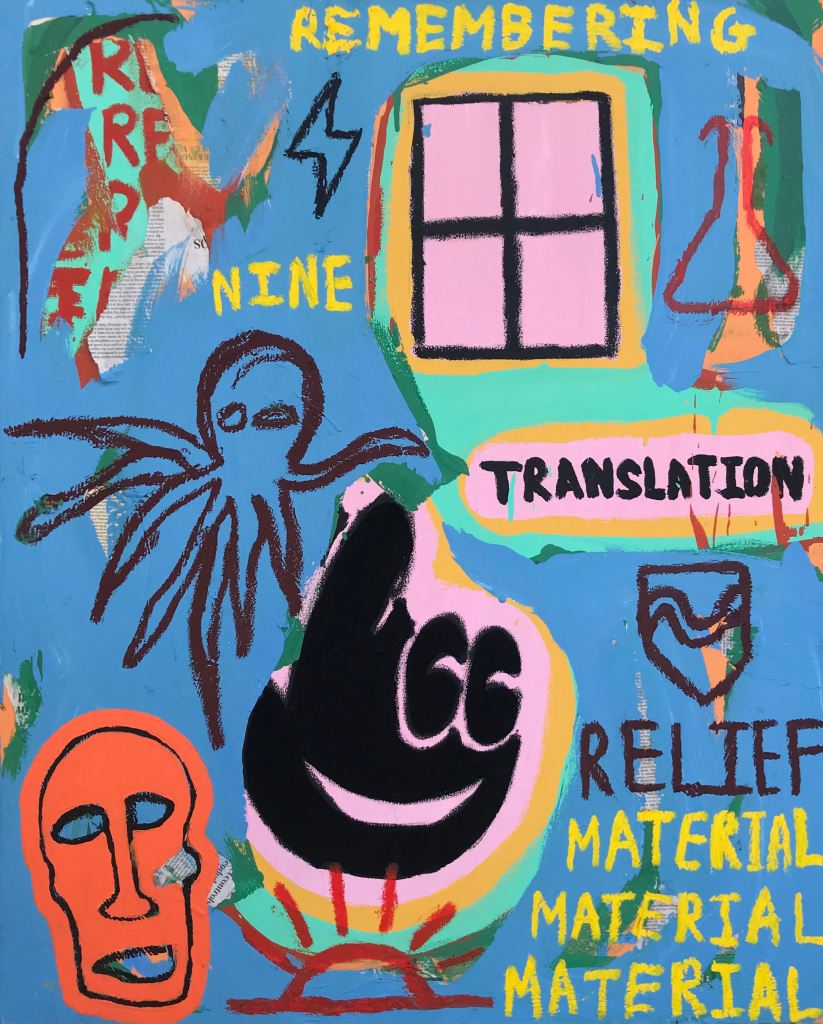

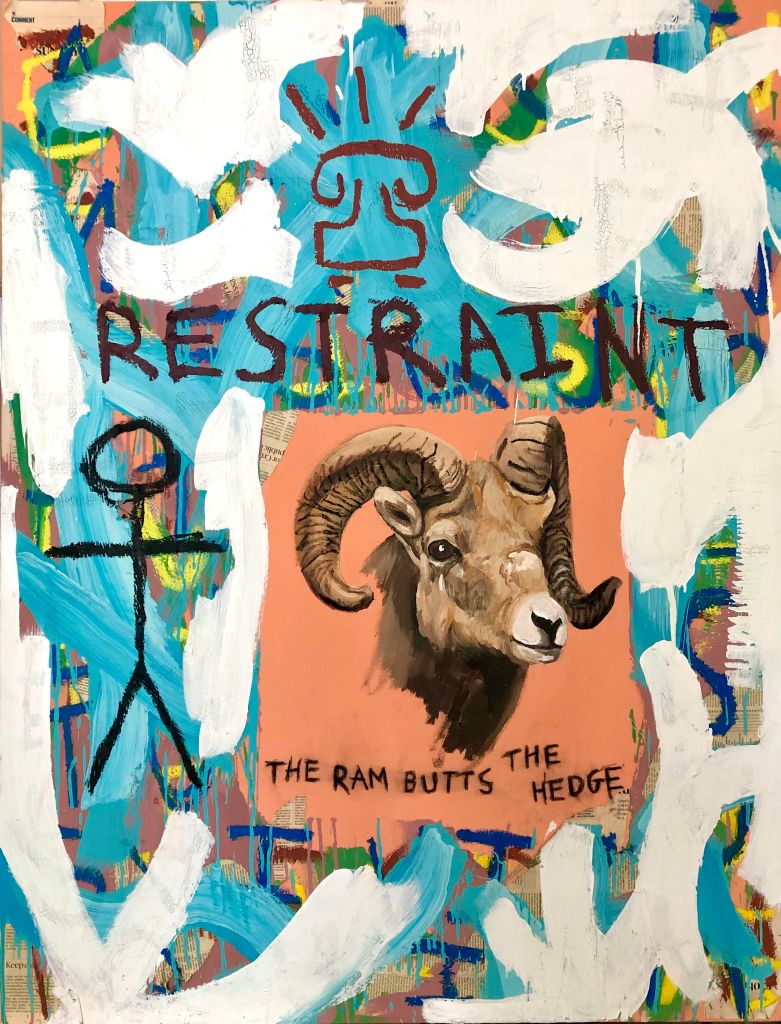

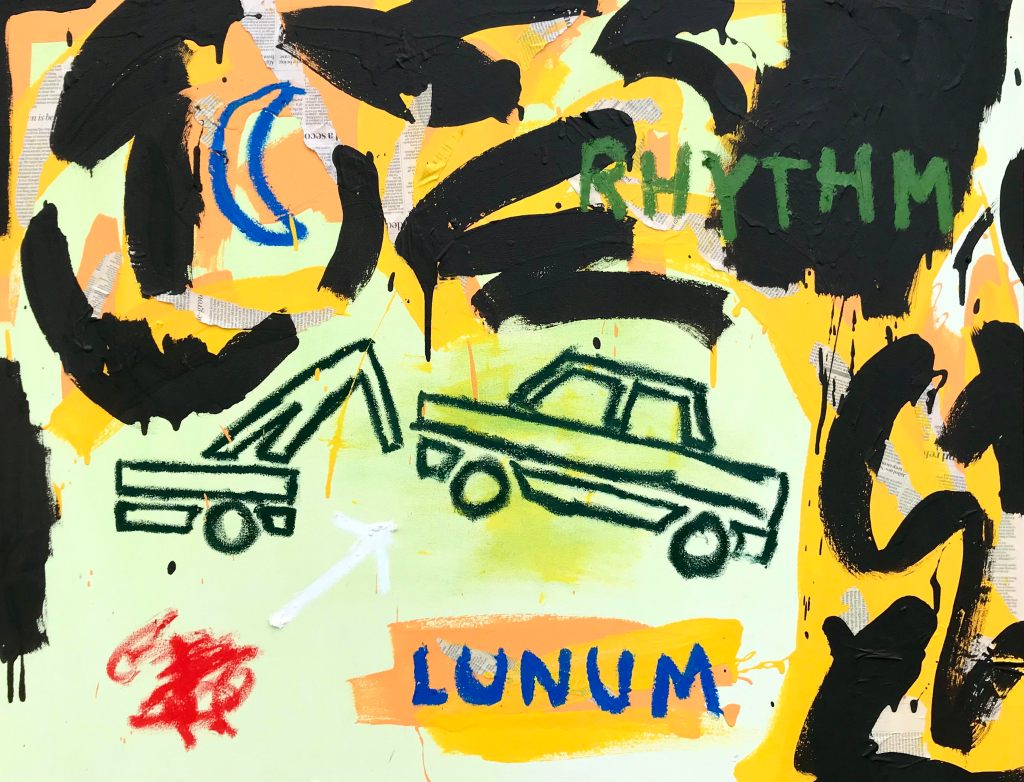

Painting’s, when understood as an asset, are merely residue of exchange, becoming an expression of the spending powers of the richest, and not as a testament to the creative conquests of humanity. They become a stock in the stock market, with variables such as the artist, their use-value, and their context coming into consideration rather than numbers on graphs. Andy Warhol’s ‘Soup Cans’ shown below, is a portrait of the painting as a marketable product, to be sold and distributed much like a can of soup in a supermarket. The only difference between the painting as an object and the object depicted within the painting is the smoke screen of the high-end art market, which congeals to form an institution, disguising exuberant spending under the sentiment of the collective fetishization of the painting.

Andy Warhol’s ‘Soup Cans’, painted in April 1962.

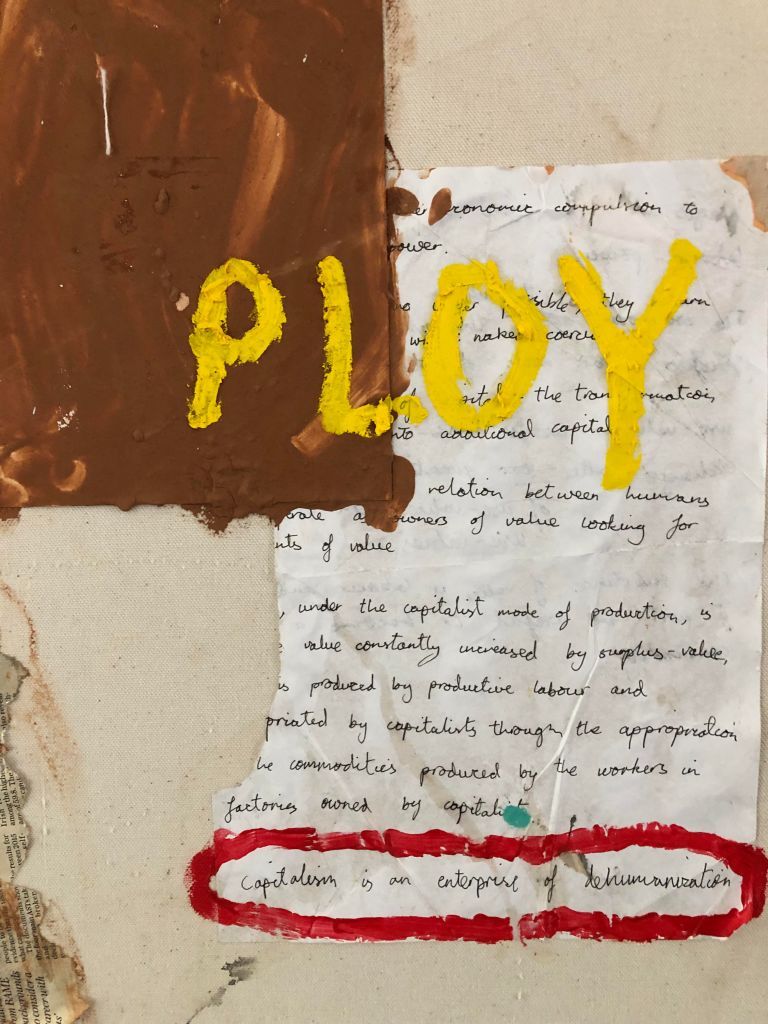

The price-form of the painting and the cost of production are totally incongruous to each other within the Modern Art Market. The cost of labour-power of a painting is a fraction of the price of what it can be sold, the rest is surplus-value under the pseudonym of intellectual labour as distinguished from profit margins. As said by Jose Maria Duran in their essay[15], ‘Artistic proprietorship is based on the assumption that what is fabricated or simply chosen – that is, the artistic object – is the material realization of the subjective and thus unique and singular intellect.’ Therefore, the fetishization of the painting must revolve around two distinct entities, the painting as object and the artist as its creator and intellectual designer. I will now discuss these subjects and their relative effect on the worth of a painting.

The Fetishization of the Painting and the Artist

The Painting

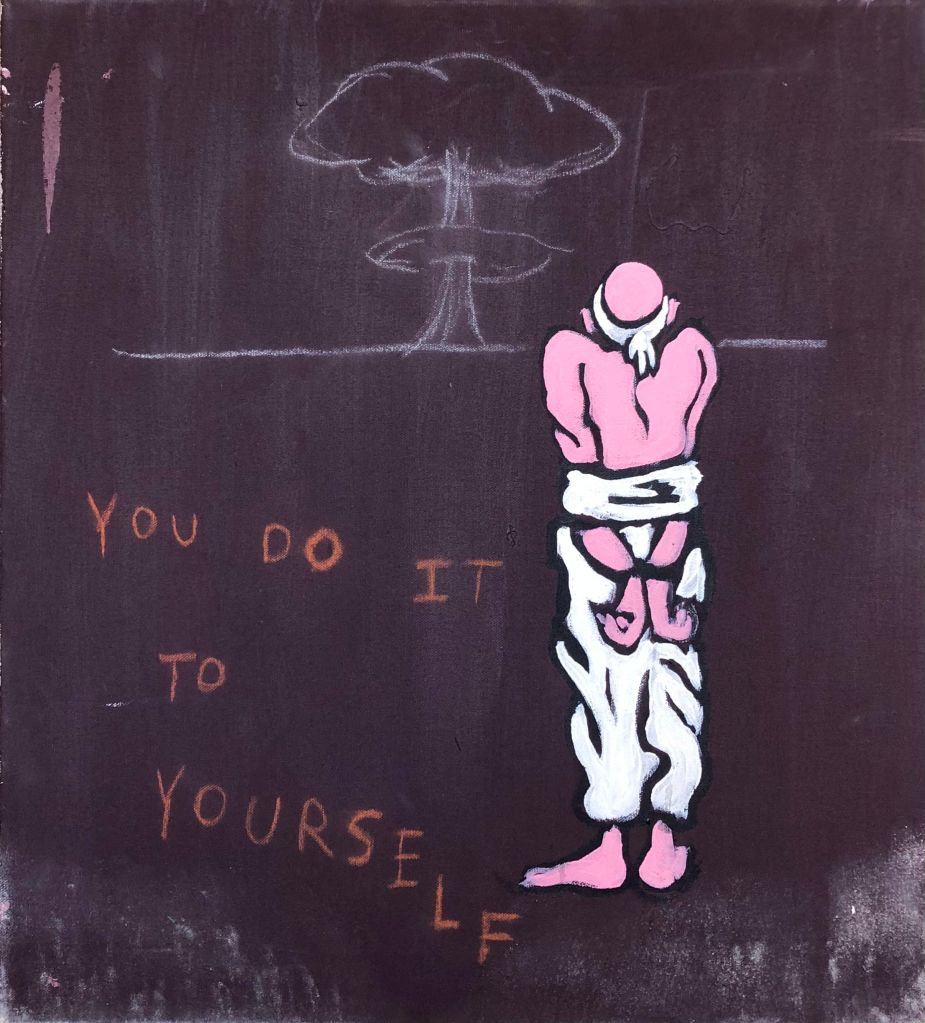

Stewart Martin said, ‘The autonomous artwork is an emphatically fetishized commodity, which is to say that it is a sensuous fixation of abstraction, of the value-form, and not immediately abstract.’[16] It is with this in mind that I begin my discussion. In reference to the aesthetic value of painting, Marcus Du Sautoy said[17],

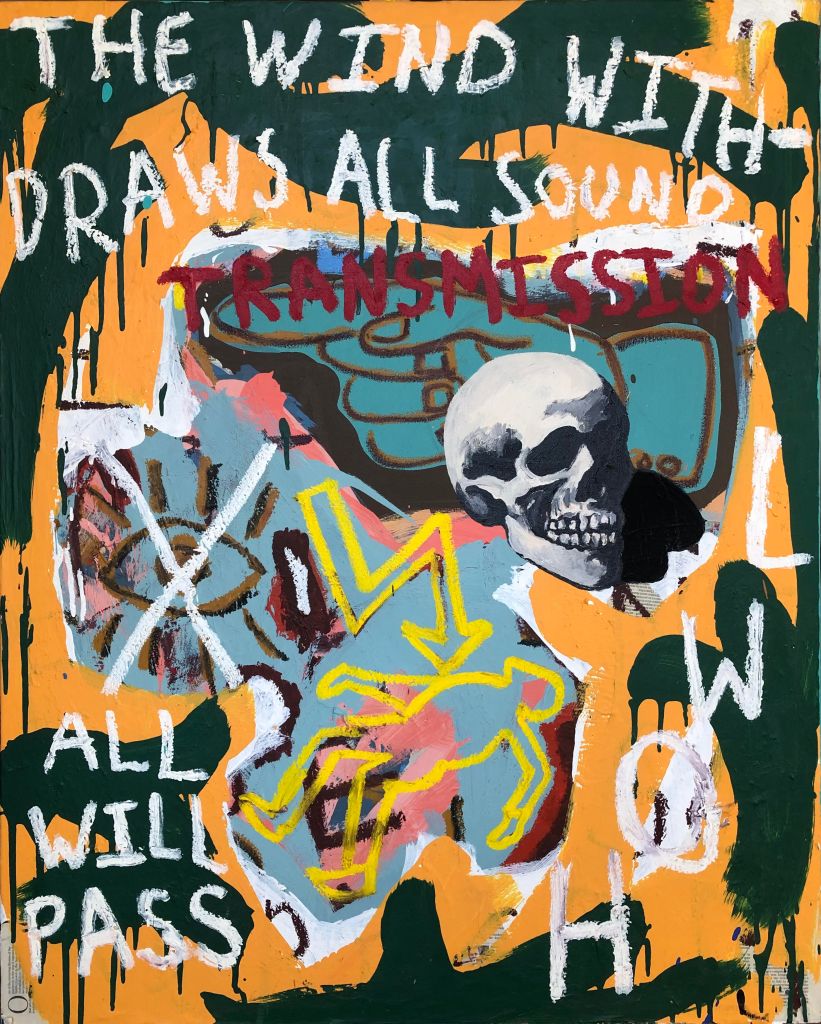

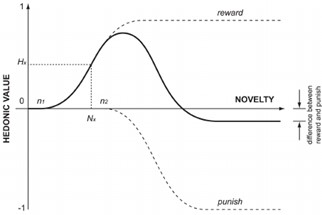

This is captured in something called the Wundt curve. If we are too habituated to the artwork around us, it leads to indifference and boredom. This is why artists never really stabilise in their work: what arouses the artist (and eventually the viewer) is something distinct. The challenge is that the push to arousal or dissonance must not be so great that we hit the downslope of the Wundt curve. There is a maximum hedonic value that the artist is after.

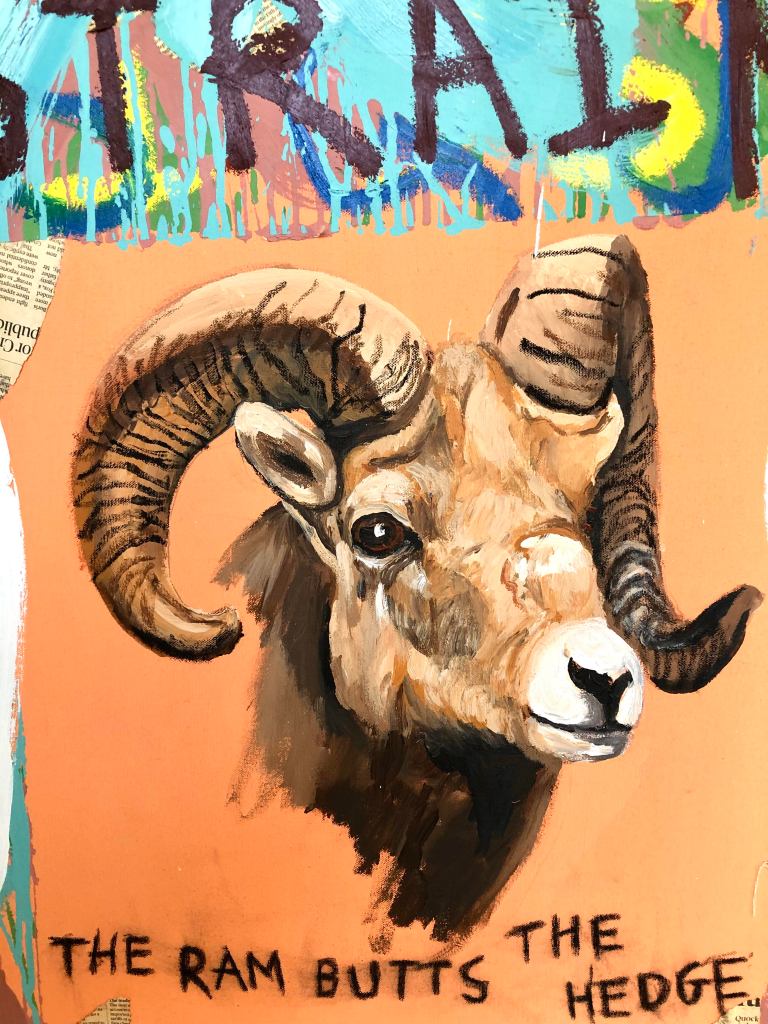

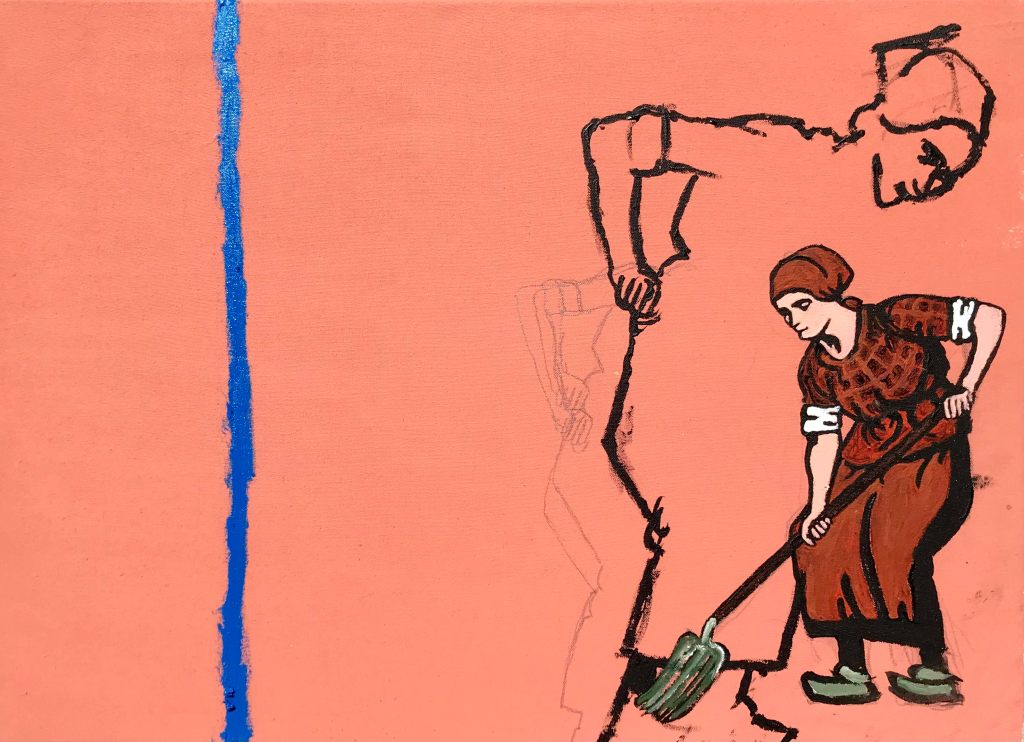

The Wundt curve, shown below, is a pictorial expression of an abstract human relationship with a painting that occurs purely within the mind of the viewer. This manifestation of emotion and provocation is singularly human.

They are thus an expression of the human condition, and the human will to create beauty. Beauty is purely abstract, i.e., within the mind of the beholder, and its translation into imagery is the signature of the artist. How original and tantalizing it is to the established doctrines of painting is the achievement of their intellectual capacity and craftmanship. Adorno said in his essay on Wagner, ‘The autonomous appearance of the artwork is dependent on the concealment of labour.’[18] As discussed, labour takes many forms, however the most valuable form of labour is that of intellectual implementation.

Sven Lutticken says[19], ‘It is the ‘archaic’ dependence on the aura of singularized and financialized objects that has made contemporary visual art a real political-economic vanguard.’ It is in this sense that painting’s epitomise value. As said by Karl Marx, ‘Human labour-power in its fluid state, or human labour, creates value, but is not itself value. It becomes value in its coagulated state, in objective form.’[20] Paintings, once finished, can be hung on a wall and observed in their unchanging state and appreciated forever, portraying value unceasingly. Marx continues, ‘Value, therefore, does not have its description branded on its forehead; it rather transforms every product of labour into a social hieroglyphic.’[21] Value is forged into the painting and then emancipated by its exchange relation as an object within a social process. I will now discuss how the artist and their presented image and identity within the social circle is involved in this impression upon the viewer.

The Artist

The artist is the nucleus of a painting’s organism. They are its producer and merchant, and the composition of various layers of paint is inextricably linked with the hand that made them. Once the painting becomes fetishized, so does the artist. The artist is an expression of the individual[22]. As said by Jose Maria Duran, ‘While wageworkers sell their labour power, artists sell the products of their labour… that is, they don’t work for someone else.’[23] The artist is therefore the productive worker at the head of their ship in which they use to navigate the marketplace of supply and demand. Once they have amassed enough demand they need only supply, and this can be done in ways much akin to a factory process of production. Artist’s such as Damien Hurst, Jeff Koons, and Andy Warhol have exploited this principle of artistic proprietorship, using their assistants as producers of the pieces, to then sell them under their name.

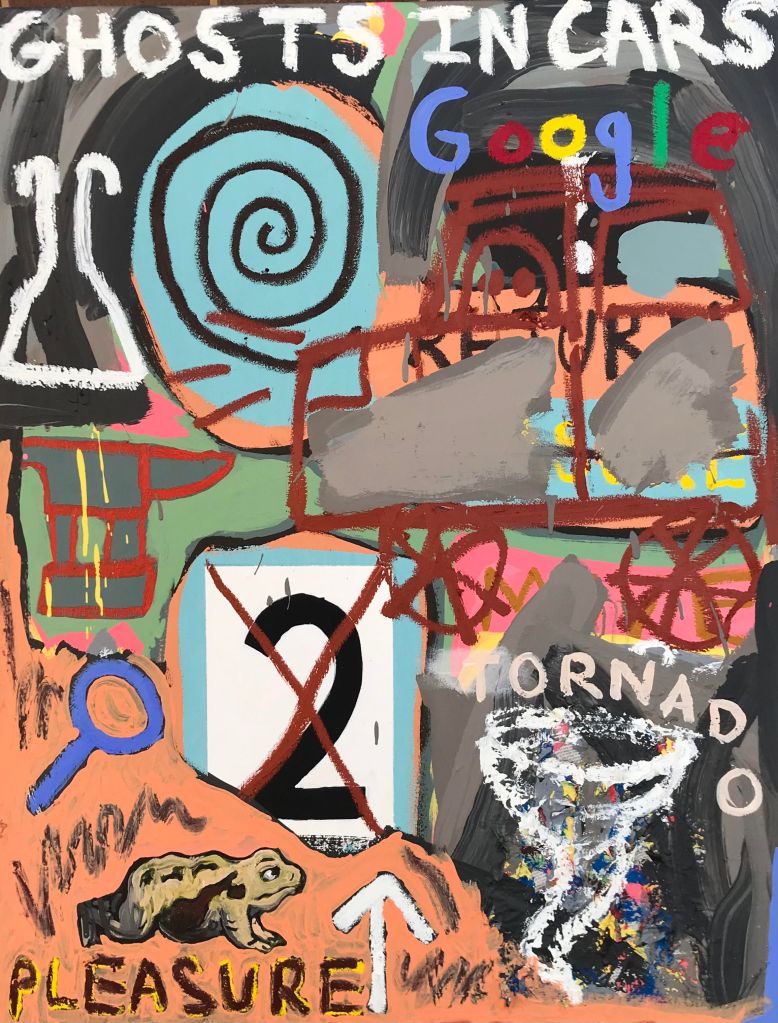

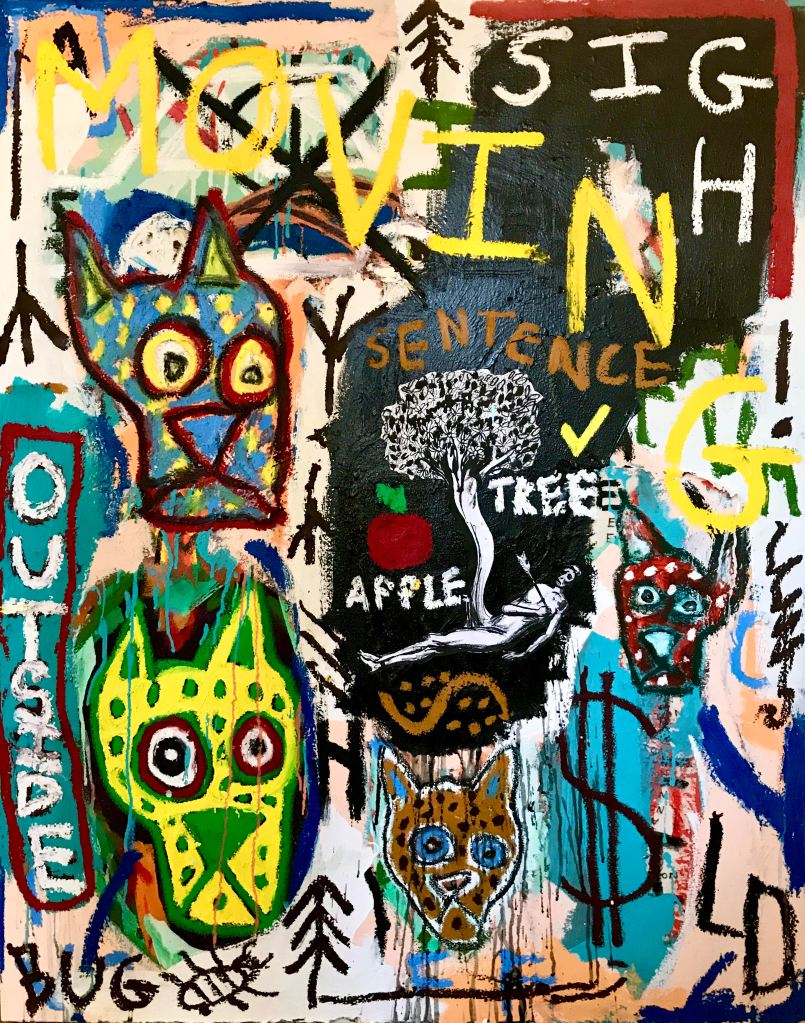

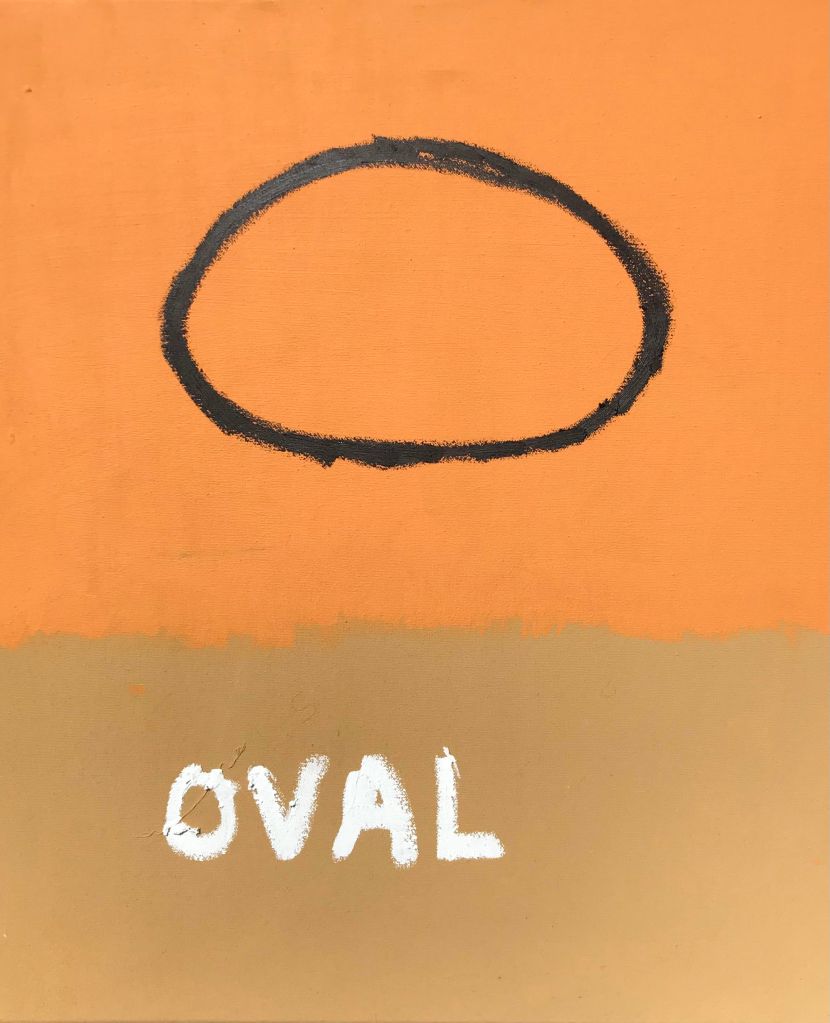

An example illustrating the division between our attraction to the intellectual origins of a work of art rather than its physical use-value is given by Marcus Du Sautoy[24], in the section on ‘Resurrecting Rembrandt’. Here, Sautoy tells us of when data scientists at Microsoft and Delft University of Technology were of the view that there was enough data for a computer algorithm to learn how to paint like Rembrandt. Sautoy says, ‘The team studied 346 paintings in total, creating 150 gigabytes of digitally rendered graphics to analyse.’ They even went so far as to imitate the surface texture of a Rembrandt painting. The final 3D printed painting consists of more than 148 million pixels, made from thirteen layers of paint-based UV ink. When the painting was exhibited in April 2016 in Amsterdam, British art critic Jonathan Jones said,

The ‘New’ Rembrandt painting created by a computer.

What a horrible, tasteless, insensitive, and soulless travesty of all that is creative in human nature. What a vile product of our strange time when the best brains dedicate themselves to the stupidest “challenges”, when technology is used for things it should never be used for and everybody feels obliged to applaud the heartless results because we so revere everything digital.

What Jones expresses in his criticism is an attachment to something that exists outside the painting but not of the painting. Although the painting and artist are inextricably linked, they are also separate entities in themselves. What Jones’ sees when looking at the computer-generated Rembrandt is not a painting that beholds quality, but a parade of the computer scientist’s abilities to stamp on the burial grounds of the dead masters and extract an abomination from its soil. He sees it as an insult, rather than a scientific breakthrough. This is not because the painting’s quality is so far from that of an original Rembrandt that it seems comical even comparing them, but because of its producer. Is this not shallow? Paradoxically, this seems to be where all of a painting’s worth resides. Not in the piece and not the artist, but the link between the two. Although this may well be true, it does not correlate to the fundamentally flawed quality of painting, the painting as asset. What is important is the context to which these two entities find their medium of exchange, the Modern Art Market.

The Modern Art Market

Beech says in regard to the price of a painting, ‘The difference in price is not extracted from labour but, as Marx puts it when talking about trade as a zero-sum game, is “coaxed” out of the pockets of another capitalist.’[25] Marx defines a capitalist as follows,

…, the possessor of money becomes a capitalist. His person, or rather his pocket, is the point from which the money starts, and to which it returns. The objective content of the circulation we have been discussing – the valorisation of value – is his subjective purpose, and it is only in so far as the appropriation of evermore wealth in the abstract is the sole driving force behind his operations that he functions as a capitalist, i.e. as capital personified and endowed with consciousness and a will. Use-values must therefore never be treated as the immediate aim of the capitalist; nor must the profit on any single transaction. His aim is rather the unceasing movement of profit-making.[26]

The Modern Art Market is the playground for capitalists to move and grow disposable wealth. Jackson Pollock’s No. 5 (1948) was sold for $140 million in 2006 by Mexican financier David Martinez. Francis Bacon’s Three studies of Lucien Freud were sold for $142.4 million at Christie’s in New York in 2013. These are only two examples of how the Modern Art Market prospers and continues to enable investors to circulate and redistribute their wealth through times of bad economic versatility, there are many more paintings that have been sold for much greater prices.

A quote from Sven Lutticken’s essay[27] is appropriate here:

As the New York collective WAGE (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) has uncovered, remuneration varies most among institutions that host performances (with The Kitchen being the best, and Performa the worst). In 2011 Andrea Fraser, a board member of WAGE, published the graph Index, which shows a correlation between the rise in the Mei Moses All Art Index and increases in US income inequality and the S&P 500 Total Return Index during the same decades. Correlation may not be causation, but it seems clear that form ‘deregulation’ has been good for the 1 per cent or the 0.1 per cent and, as a consequence, for the art market. In other words, ‘what has been good for art has been disastrous for the rest of the world.’

To understand and analyse this quote further I will use the Marxist Immiseration Thesis. The Immiseration Thesis states that the nature of capitalist production stabilizes real wages, reducing wage growth relative to total value creation in the economy, leading to the increasing power of capital in society. When comparing this thesis to the Modern Art Market it is clear the extent to which the gap has grown between retail and high-end art, analogous of wage gaps. Although the stabilisation of real wages is important to regulate inflation rates, it is only useful to a certain degree before it becomes debilitating, and juxtaposing the rate of growth of the minimum wage to the rate of price increase of painting’s being sold in today’s Modern Art Market we see the blatant misdistribution of wealth clearly and realistically. As rich capitalist’s use disposable income to buy paintings as assets, those below the poverty line struggle to afford food.

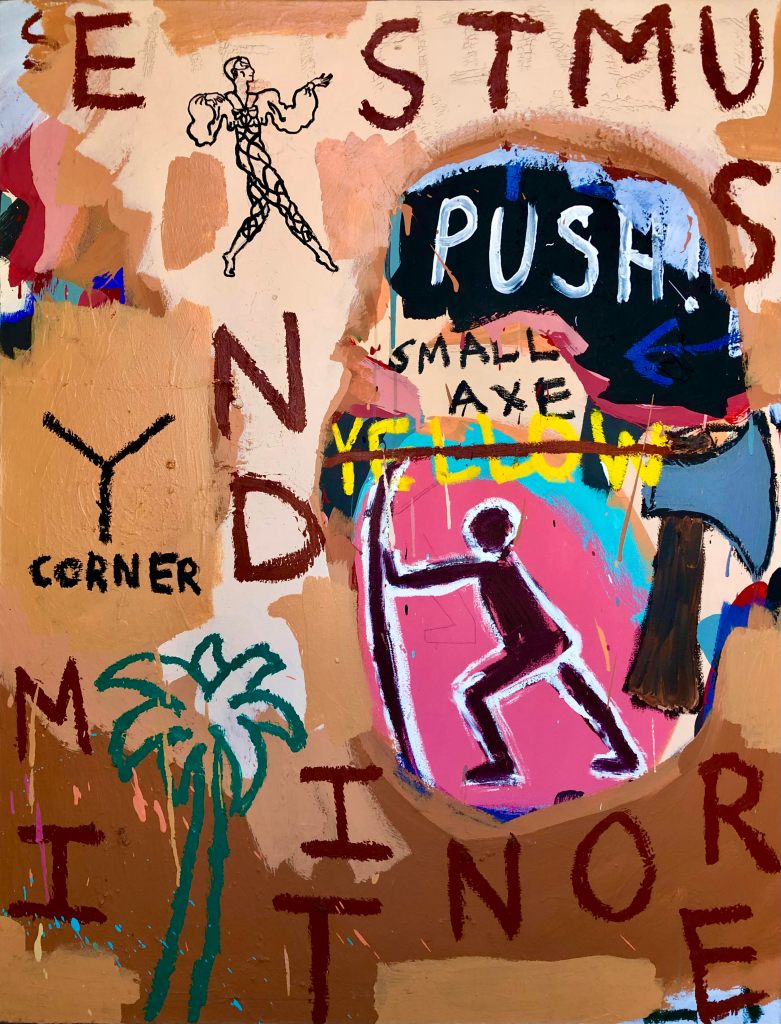

The irony of the fetishization of paintings and the Modern Art Market is most elegantly displayed in the documentary Made You Look directed by Barry Avrich. In this, we are told the tale of when $80 Million worth of fake paintings were sold by the oldest gallery in New York, the Knoedler Gallery, in the span of 14 years between 2000 and 2014. The fake paintings were made by Chinese artist Pei-Shen Qian, who had mastered the techniques of several world-famous artists, such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, etc. to then give them to Glafira Rosales. Glafira’s husband had acquired canvas made from the same period as paintings made by the copied artists, along with nails, to improve the fake painting’s authenticity. Glafira had designed an elaborate story as to the origins of these mysterious paintings to then sell them to the Knoedler Gallery who would then go on to resell them for up to $8.3 Million. Scholars of Rothko believed the paintings were real, testament to their quality, however, when put under the scrutiny of scientist’s they were easily recognised as fake. This shows how transparent the Modern Art Market can be, revealing its inner organs of avarice, cheating, and lying, surviving on the fetishized painting and the will for the accumulation of capital. As said by Marx, ‘Circulation sweats money from every pore.’[28]

Fake Mark Rothko painting painted by Pei-Shen Qian which eventually sold for $8.3 Million.

Conclusion

When researching the Modern Art Market and understanding it as another institution for the circulation of wealth, I found it to have many problems. There is a lack of responsibility inherent at its core, allowing no pang of moral conscience throughout the distribution of paintings due to their fetishized nature and the scandal of its buoyancy due to its perpetual survival through economic recession by the constant flow of money into its system. One can only shudder at the prices of some of the more well-known artists painting’s, wondering how a bit of canvas can be worth more than a house. The Modern Art Market is only one example of a much larger problem, the elitism of the upper class and their dominance over society. It is this that was at the core of my essay, and it is a shame that the painting as asset allows them to use it to redistribute and enlarge their capital, condescending the beauty of their nature. I feel purged of the idea that price equates to worth. Rather, price only means avarice, and avarice means someone is being cheated for another’s gain.

Bibliography

- Avrich, Barry, Director of Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art (2020)

- Baldwin, James Mark, History of Psychology: A Sketch and an Interpretation, Vol. 1 Classics in the History of Psychology — Baldwin (1913) Volume I, Chapter 1 (yorku.ca)

- Duran, Jose Maria, Artistic Labor and the Production of Value: An Attempt at a Marxist Interpretation: Full article: Artistic Labor and the Production of Value: An Attempt at a Marxist Interpretation (brighton.ac.uk)

- Kahn, Nathaniel, Director of The Price of Everything (2018)

- Lutticken, Sven, The Coming Exception: Art and the Crisis of Value: Sven Lütticken, The Coming Exception, NLR 99, May–June 2016 (brighton.ac.uk)

- Marx, Karl, Capital Volume 1, edition first printed in Pelican Books 1976 and reprinted in Penguin Classis 1990.

- Sautoy, Marcus Du, The Creativity Code, How AI is Learning to Write, Painting and Think, first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019.

- Tolstoy, Leo, What is Art?, translation by Alymer Maude (1899): Euthyphro, by PlatoTranslated by Benjamin Jowett (mnstate.edu)

- Wilken, Karen, Braque (Modern Masters), published in 1992.

References

[1] Karl Marx, Capital vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg.125

[2] Karl Marx, Capital vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg.126

[3] Karen Wilkin and Georges Braque, Braque (Modern Masters), in section on his diaries

[4] Leo Tolstoy, What is Art?

[5] Marcus Du Sautoy, The Creativity Code, pg.142

[6] “Colour is a power which directly influences the soul. Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the band which plays, touching one key or another to cause vibration in the soul.” – Wassily Kandinsky

[7] James Mark Baldwin, History of Psychology: A Sketch and an Interpretation

Volume I, Chapter 1, Introduction: Racial and Individual Thought

[8] “Art and money have always gone hand in hand. It is very important for good art to be expensive. You only protect things that are valuable. If something has no financial value people don’t care. They would not give it the necessary protection. The only way for cultural artifacts to survive is for them to have a commercial value.” – Simon de Pury, Auctioneer, from documentary The Price of Everything.

[9] Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg. 138

[10] Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg.126

[11] “There’s a lot more money selling a painting the second or third time rather than the first.” – Mary Boone, Art Gallerist, The Price of Everything.

[12] Jose Maria Duran, Artistic Labor and the Production of Value: An attempt at a Marxist Interpretation

[13] “We have seen that when Commodities are in relation of exchange, their exchange-value manifests itself as something totally independent of their use-value.” – Karl Marx, Capital vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg. 128

[14] Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 1, The Process of Exchange, pg. 184

[15] Jose Maria Duran, Artistic Labor and the Production of Value: An attempt at a Marxist Interpretation

[16] Sven Lutticken, The Coming Exception: Art and the Crisis of Value

[17] Marcus Du Sautoy, The Creativity Code, Learning From the Masters, pg.139

[18] Sven Lutticken, The Coming Exception: Art and the Crisis of Value

[19] Sven Lutticken, The Coming Exception: Art and the Crisis of Value

[20] Karl Marx Capital Vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg. 142

[21] Karl Marx Capital Vol. 1, Commodities and Money, pg. 167

[22] “I will try to explain the term “individuation” as simply as possible. By it I mean the psychological process that makes of a human being an “individual”-a unique, indivisible unit or “whole man.” – Carl Jung on individuation from a lecture at the Eranos Meeting at Ascona

[23] Jose Maria Duran, Artist Labour and the Production of Value: An Attempt at a Marxist Interpretation

[24] Marcus Du Sautoy, The Creativity Code, Resurrecting Rembrandt, pg. 126

[25] Sven Lutticken, The Coming Exception, Art and the Crisis of Value

[26] Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 1, The General Formula for Capital, pg. 254

[27] Sven Lutticken, The Coming Exception, Art and the Crisis of Value

[28] Karl Marx Capital Vol. 1, Money or the Circulation of Commodities, pg. 208